Inflation is one of the oldest and most well known adversaries faced by investors. Simply put it measures the change in price of goods and services that we purchase or consume including food, fuel, utilities, housing, clothing, entertainment, etc. That being said, investors must achieve a rate of return in excess of the rate of inflation in order to improve their purchasing power.

Inflation is a natural consequence of a credit based economy such as the one we live in. When individuals and businesses borrow money the resulting loan becomes a deposit, and this newly created money is an increase in the overall money supply. All things being equal there is now more money available to purchase a set amount of goods and services. In this situation basic economic theory tells us that prices will increase as demand exceeds supply (this is referred to as demand-pull inflation). [1]

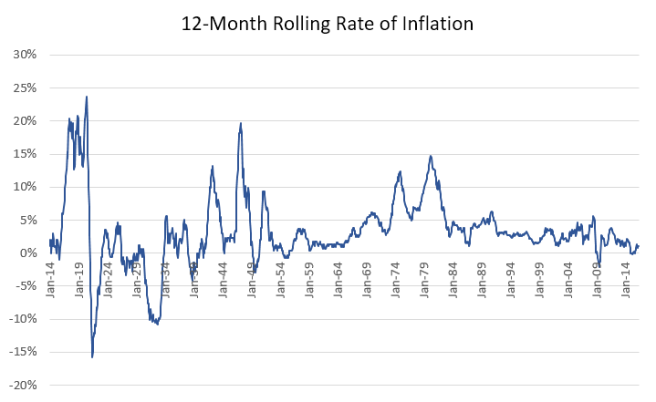

As we borrow and spend more, inflation continues to be an ever present force in our economy. Since 1913 inflation has ticked along at approximately 3.1% per year. More recently, over the past 50 years, it has persisted at a slightly higher 4.1% annualized rate. These numbers seem small, but when compounded over very long periods of time, say 20, 30 or 40 years, the numbers can become quite large. Anyone who has examined the impact of a 1% annual expense ratio on their investment returns can attest to this.

***

General Electric has been in the news recently for announcing that the company is reviewing the way that it compensates employees. This entails cutting the annual pay increase (typically around 2% to 3% annually) and substituting the lost income with other benefits. [2] It’s difficult to gauge whether this development will be positive for employees, and more than likely hinges on the form that these other benefits will take and how they align with employee values. However, the significance of this sentiment should not be underestimated because it signals a new direction for one of America’s largest and oldest corporations, a path that other US companies could follow if they haven’t already.

“You can’t really do a lot with the annual raise,” said Evren Esen, director of survey programs at the Society for Human Resource Management. When the economy is decent, annual pay adjustments come in at 1 percentage point or 2 percentage points ahead of inflation for a given year. That doesn’t go far. Employees expect to get at least the cost of living adjustment, and a measly 2 percent increase in pay doesn’t do much to encourage or change employee behavior. At best, the most stellar employees are getting a 5 percent raise, only slightly more than their average colleagues, who in 2016 can expect a 3.1 percent bump—if that. In the end, it’s too small an increase to make a difference. [3]

I won’t argue with the former part of that statement. Experiencing a pay increase of only a few percent in any given year isn’t exactly motivating. But claiming that the annual raise is too small to make a difference ignores the long term, big picture consequences of eliminating such compensation, and its effect should not be discounted. Over long periods of time this small annual increase actually works to keep employee wages in line with the rising cost of living brought about by inflation. Although it has been low in recent years, we shouldn’t forget that inflation isn’t constant, but instead ebbs and flows over time.

At present this is a difficult scenario to comprehend. Since the end of the recession in March 2009 inflation has ticked along at an annualized rate of 1.7%–far lower than the 4.1% the US has experienced over the past 50 years. Given these facts it’s rather easy to justify the insignificance of the annual raise. But we shouldn’t let our behavioral biases influence expectations. Operating under the assumption that the current low rate of inflation will continue indefinitely into the future represents a classic example of confirmation bias. If history has taught us anything it is that nothing lasts forever. Sooner or later when borrowing begins to increase there will be more money available than goods and services supplied. Demand will outstrip supply and the cost of living (inflation) will increase at a higher rate.

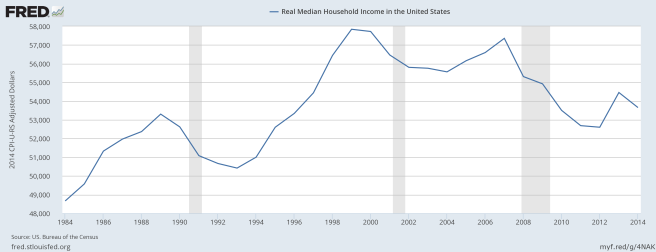

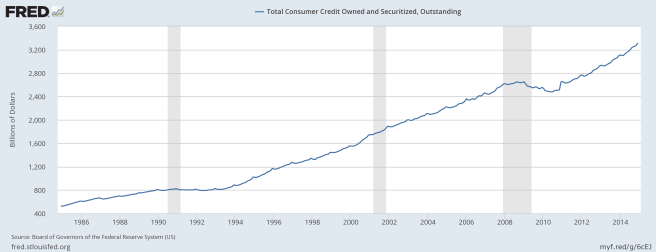

One argument to consider is that reduced pay could lead to less spending and less demand, and therefore maintain the current low rate of inflation–everything should balance out. Theoretically, when folks make less money they should also spend less, and prices should rise at a lower rate, if at all. However, history has shown that we do not, in fact, spend less. Remember that we live in a credit based economy, and additional money is created when borrowers take out loans. Between 1984 and 2014 median household income in the US grew at an annualized rate of only 0.3% after inflation–it has kept up with the cost of living and only just. Meanwhile consumer credit grew at an annual rate of 3.7% after inflation over the same period. [5,6] Those numbers should be telling. In real, after inflation terms, income has been relatively flat and consumers have turned to debt to finance their lives.

Ironically the voice of reason regarding employee compensation would appear to be coming from the head of one of Wall Street’s biggest banks. JP Morgan CEO Jaime Dimon recently went on public record stating that his company would increase the pay of 18,000 employees. In doing so he isn’t just making a bet on his employees, he’s making a bet on the future of the US economy

A pay increase is the right thing to do. Wages for many Americans have gone nowhere for too long. Many employees who will receive this increase work as bank tellers and customer service representatives. Above all, it enables more people to begin to share in the rewards of economic growth.

And it’s good for our company, helping us attract and retain talented people in a competitive environment. While businesses, including ours, are understandably cautious when it comes to expenses, there are good expenses (investments that will pay off in the long run) and bad expenses (waste and inefficiencies). We have never hesitated to invest aggressively if we thought it would improve our long-term prospects. [7]

I want to be clear. I don’t view the annual raise as an entitlement, but see the elimination of such a benefit as a means of marginalizing the long-term welfare, not just of consumers and employees, but of the US economy as a whole. It is scenarios such as this that have pushed me to take control of my own finances and encourage me to continue learning. Perhaps that is the bigger lesson for consumers. Understanding your values, living below your means and spending prudently is likely to become more important in the future if it hasn’t already.

The direction of the annual raise at GE is unclear as the company would appear to only be in the early stages of their decision. The reduction itself may already be happening in certain industries and may (or may not) spread to others. In any case, elimination of the annual raise is a reduction in pay, and will likely make the personal finances of employees more difficult. It is hard to imagine that taking money out of the pockets of consumers, in the long-run, will be beneficial to our economy. A truly healthy economy requires that both consumers and businesses be on sound financial ground.

References

1. Roche, Cullen. Pragmatic Capitalism. Palgrave Macmillan. New York, NY. 2014. pp. 150-155.

2. Clough, Rick. GE Considers Scrapping the Annual Raise. Bloomberg. June 6, 2016. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-06-06/ge-studies-scrapping-annual-raise-in-nod-to-shifting-priorities.

3. Greenfield, Rebecca. Say Goodbye to the Annual Pay Raise. Bloomberg. June 21, 2016. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-06-21/say-goodbye-to-the-annual-pay-raise.

4. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIAUCNS

5. Median Household Income: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MEHOINUSA672N

6. Total Consumer Credit: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TOTALNS

7. Dimon, Jaime. Why We’re Giving Our Employees a Raise. New York Times. July 12, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/12/opinion/jamie-dimon-why-were-giving-our-employees-a-raise.html

What I’m Reading

Evidence-Based Investing Requires Less Religion and More Reason (Wes Gray)

podcast: China and the History of the US Dollar w/ Richard Duncan (The Investors Podcast)

Vanguard, the Unlikely Savior of Active Management (Bloomberg)

Why Buffett’s Million-Dollar Bet Against Hedge Funds Was a Slam Dunk (Roger Lowenstein)